The existence of the historical Jesus is the most well-documented and preserved evidence in the ancient history of mankind.

Taking into account the over 24,600 partial or complete manuscripts of the 27 books of the New Testament as a historical text, it unequivocally stands out as the best source of the historical Jesus.

The second-best documented manuscript of ancient history is the “Iliad and the Odyssey,” by Homer, with only 643 manuscripts.

The New Testament isn’t just a religious text; those 27 books, and especially the Gospels and Paul's letters, offer detailed accounts of Jesus’ life, teachings, crucifixion, and resurrection. While they’re indeed religious texts, many scholars treat them as historical sources based on the fact that they were written within decades of Jesus’ life and also contain references to other real historical figures like Pilate, Herod, or Caiaphas.

Jesus of Nazareth is widely regarded by historians as a real historical figure.

There are several ancient non-Christian writers who mention Jesus, confirming he was known outside the early church.

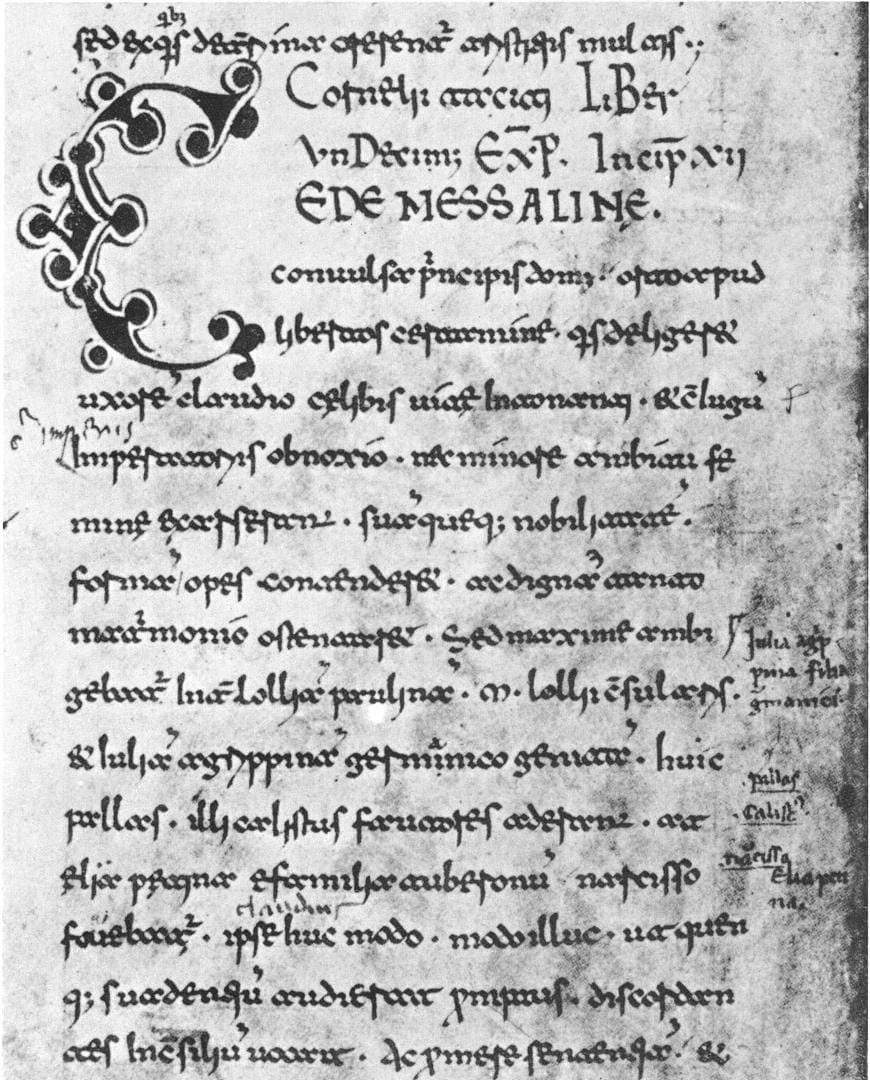

- One of the earliest and most significant non-Christian references to Jesus is found in the Annals of the Roman historian Cornelius Tacitus, written around AD 115–117—approximately 85 years after Jesus' crucifixion. Tacitus mentions Christ while recounting how Emperor Nero falsely accused Christians of starting the great fire of Rome in AD 64, a blaze that many suspected Nero had orchestrated himself.

A manuscript copy of Tacitus' Annals from the 11th century. Image credit of Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain.

Consequently, to get rid of the report, Nero fastened the guilt and inflicted the most exquisite tortures on a class hated for their abominations, called Christians by the populace. Christus, from whom the name had its origin, suffered the extreme penalty during the reign of Tiberius at the hands of one of our procurators, Pontius Pilatus, and a most mischievous superstition, thus checked for the moment, again broke out not only in Judaea, the first source of the evil, but even in Rome, where all things hideous and shameful from every part of the world find their centre and become popular. Accordingly, an arrest was first made of all who pleaded guilty; then, upon their information, an immense multitude was convicted, not so much of the crime of firing the city, as of hatred against mankind. Mockery of every sort was added to their deaths. Covered with the skins of beasts, they were torn by dogs and perished, or were nailed to crosses, or were doomed to the flames and burnt, to serve as a nightly illumination, when daylight had expired.

Documentation is available in the MIT archives; see the link below. https://classics.mit.edu/Tacitus/annals.11.xv.html

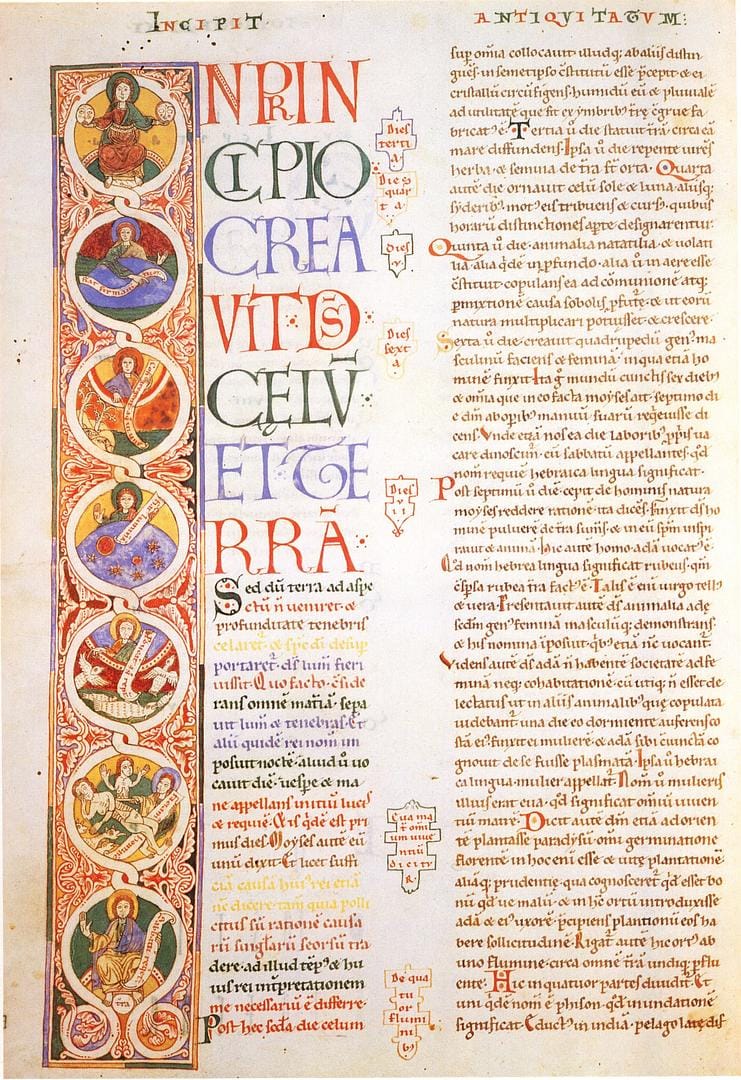

- One of the next significant ancient sources that references Jesus as a historical figure is found in the writings of the Jewish historian Flavius Josephus, particularly in his work Antiquities of the Jews.

An illustrated page from a Latin translation of Josephus’ Antiquities of the Jews, housed in the Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Florence. Image: Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain.

Writing in the late first century, Josephus includes two notable passages that have direct reference to Jesus. Antiquities of the Jews – Book 18, Chapter 3, Paragraph 3. Commonly known as the “Testimonium Flavianum”

Now there was about this time Jesus, a wise man, if it be lawful to call him a man; for he was a doer of wonderful works, a teacher of such men as receive the truth with pleasure. He drew over to him both many of the Jews and many of the Gentiles. He was [the] Christ. And when Pilate, at the suggestion of the principal men amongst us, had condemned him to the cross, 9 those that loved him at the first did not forsake him; for he appeared to them alive again the third day; 10 as the divine prophets had foretold these and ten thousand other wonderful things concerning him. And the tribe of Christians, so named from him, are not extinct at this day.

Documentation is available in the Gutenberg archives; see the link below. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/2848/2848-h/2848-h.htm#link182HCH0003

Most scholars—both Christian and non-Christian—agree that the Greek version of this passage was likely altered by a Christian scribe in antiquity, as it's unlikely that Josephus, a Jewish historian, would have written, “He was the Christ.” While the text may have been modified, it is widely believed to preserve a genuine historical reference to Jesus at its core. Over the years, scholars have proposed various reconstructions of what the original wording might have been. Then, in the 1970s, an Arabic version of the passage was discovered and published—free from the pro-Christian interpolations. It reads:

At this time there was a wise man who was called Jesus. His conduct was good, and [he] was known to be virtuous. And many people from among the Jews and the other nations became his disciples. Pilate condemned him to be crucified and to die. But those who had become his disciples did not abandon his discipleship. They reported that he had appeared to them three days after his crucifixion, and that he was alive; accordingly he was perhaps the Messiah concerning whom the prophets have recounted wonders.

See ➡️ Schlomo Pines, An Arabic Version of the Testimonium Flavianum and Its Implications. (Jerusalem: Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities, 1971), 9-10.

Historian Paul L. Maier observes, “Clearly this version of the passage is expressed in a manner appropriate to a non-Christian Jew, and it corresponds almost precisely to previous scholarly projections of what Josephus actually wrote.” ➡️ Paul L. Maier, Eusebius: The Church History. (Grand Rapids: Kregel Publications, 2007), 337.

Antiquities of the Jews – Book 20, Chapter 9, Paragraph 1

Mentions "James, the brother of Jesus who was called the Christ."

Festus was now dead, and Albinus was but upon the road; so he assembled the sanhedrim of judges, and brought before them the brother of Jesus, who was called Christ, whose name was James, and some others, [or, some of his companions]; and when he had formed an accusation against them as breakers of the law, he delivered them to be stoned:

Documentation is available in the Gutenberg archives; see the link below.

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/2848/2848-h/2848-h.htm#link202HCH0009

Josephus does not mention Christians as an organized group in detail, but these two passages indirectly support the existence of the early Christian movement.

He refers to the Sadducees, Pharisees, Essenes, and other Jewish sects far more than to the Christians—likely due to Christianity still being a small movement during his lifetime (37–100 AD).

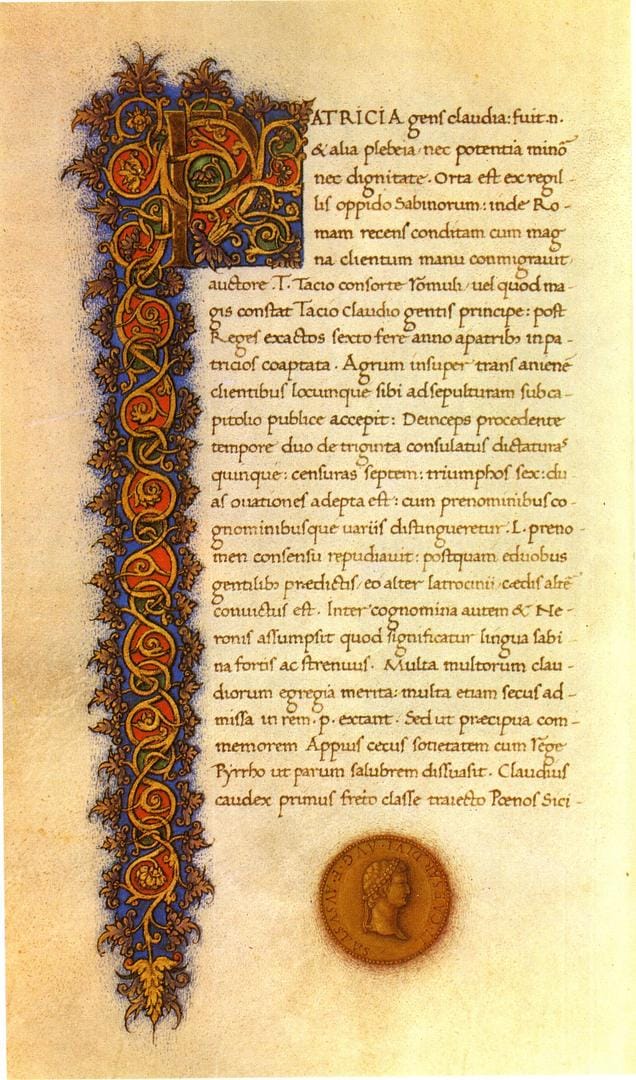

- The next notable passage from ancient history that mentions Jesus comes from the Roman historian Suetonius, in his work De Vita Caesarum (Latin for The Life of the Caesars), commonly known as The Twelve Caesars.

Suetonius wasn’t writing theology or promoting any religious agenda. His goal was to document the personalities, scandals, and political acts of the emperors. This makes his references to Christianity especially valuable—because they are neutral or hostile and therefore less biased.

A page from Suetonius, De vita Caesarum (Lives of the Caesars), in the Berlin State Library. Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

He banished from Rome all the Jews, who were continually making disturbances at the instigation of one Chrestus.

Documentation is available in the Gutenberg archives; see the link below.

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/6400/6400-h/6400-h.htm#link2H_4_0006

There is an important note to make that in Latin we can read “Iudaeos impulsore Chresto assidue tumultuantis Roma expulit.”

Scholars widely agree that “Chrestus” is a misspelling or phonetic variant of Christus (Latin for Christ).

It was common for non-Christians in the 1st and 2nd centuries to misunderstand the name “Christos” and write it as “Chrestos” (a more common name or term in Roman society).

Another account is available in Suetonius's letter to Nero. We can read as follows:

“Punishment was inflicted on the Christians, a class of men given to a new and mischievous superstition.”

Even though there is no historical evidence that Christians were responsible for the Great Fire of Rome in 64 AD, they were nonetheless persecuted by the authorities—likely in connection with Nero’s response to the disaster. This is what Suetonius refers to in his writings.

Documentation (letter) is available in the archives; see the link below.

https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Suetonius/12Caesars/Nero*.html

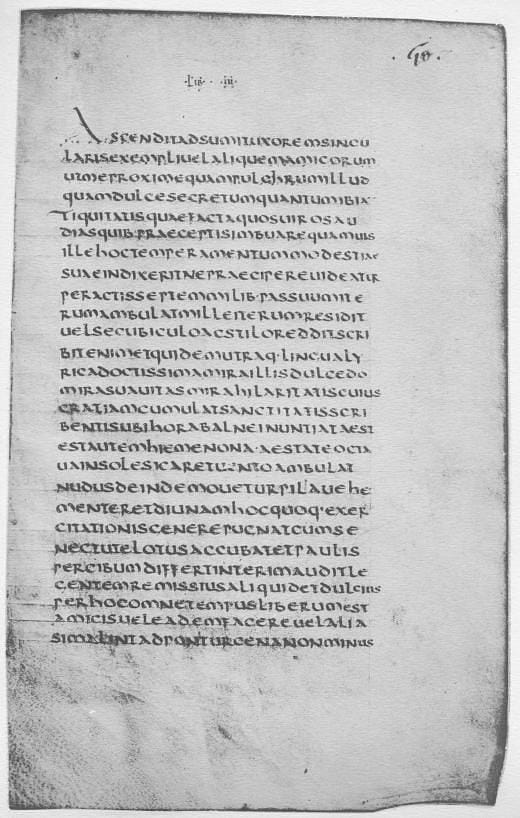

- When considering the historical evidence for the existence of Jesus of Nazareth and the early Christian movement, it’s important to look beyond the New Testament as we dive deeper into the records of the ancient world. Among the most valuable sources is a letter written by Pliny the Younger, a Roman governor in Asia Minor, to Emperor Trajan around 112 AD.

This document is not Christian, nor is it written in defense of the faith. Instead, it is a practical administrative report—yet it provides remarkable confirmation of the existence, worship, and resilience of the early Christian community.

VIth-century from Pliny’s Letters. Image Credit: Project Gutenberg

His Letter 10.96 (commonly titled Epistulae X.96) is particularly significant because it contains one of the earliest non-Christian references to followers of Christ.

“They affirmed, however, that the whole of their guilt or error was, that they were in the habit of meeting on a fixed day before it was light, when they sang in alternate verses a hymn to Christ as to a god…”

This is significant. Pliny—a pagan Roman—testifies that Christians were not merely honoring Jesus as a moral teacher or martyr. They were worshipping Him as divine, offering hymns in a liturgical format typically reserved for deity.

This directly confirms what the New Testament teaches and refutes later claims that the divinity of Christ was a later invention. The belief in Jesus’ divine status was firmly in place in the early 2nd century—within living memory of the apostles.

Documentation is available in the Attalus archives; see the link below.

https://www.attalus.org/old/pliny10b.html#96

- Another ancient source that portrays the life and crucifixion of Jesus of Nazareth apart from the Christian texts and Roman records, but opens up another stream of testimony that is often overlooked, is the Jewish Rabbinic literature, particularly the Talmud.

Although some of these references are brief, cryptic, and sometimes even hostile, they are valuable for us based on what they unintentionally confirm—that Jesus of Nazareth was a known historical figure.

One of the passages from the Talmud presents:

“On the eve of Passover, Yeshu was hanged. For forty days before the execution took place, a herald went forth and cried, ‘He is going to be stoned because he has practiced sorcery and enticed Israel to apostasy.’” - Sanhedrin 43a

Scholars have identified the following references in the Talmud that some conclude refer to Jesus:

- Jesus as a sorcerer with disciples (b Sanh 43a–b)

- Healing in the name of Jesus (Hul 2:22f; AZ 2:22/12; y Shab 124:4/13; QohR 1:8; b AZ 27b)

- As a Torah teacher (b AZ 17a; Hul 2:24; QohR 1:8)

- As a son or disciple that turned out badly (Sanh 103a/b; Ber 17b)

- As a frivolous disciple who practiced magic and turned to idolatry (Sanh 107b; Sot 47a)

- Jesus' punishment in afterlife is to be boiled for eternity in excrement (b Git 56b, 57a)

- Jesus' execution (b Sanh 43a-b)

- Jesus as the son of Mary (Shab 104b, Sanh 67a)

Research based on the book - “Jesus In The Talmud” by Peter Schafer

“The Talmudic stories about Jesus are not meant to preserve history, but they do bear witness to his existence as a real person who caused serious disruption.”

Most modern scholars, even those critical of Christian tradition, agree that these Talmudic passages reflect a historical memory of Jesus, albeit filtered through post-temple Jewish resistance to Christianity.

Bart Ehrman (Agnostic Scholar):

“There is no doubt that the Talmud refers to Jesus, although the references are not historically reliable. They show, however, that Jesus was known in Jewish circles.”

(Did Jesus Exist?, 2012)

- Thallus has been the earliest non-Christian writer who refers to the historical Jesus of Nazareth.

Thallus was a historian writing in Greek; scholars’ estimates his work around AD 50–60, which would make him one of the earliest known secular chroniclers of the events surrounding the life of Jesus. Unfortunately, his writings are lost; we know of him only through quotations and references in later authors.

The example reference work of Thallus explicitly shows how fragile the ancient documents were.

The most important reference to Thallus comes from the early Christian historian Julius Africanus (c. AD 160–240), preserved in George Syncellus’ Chronography (9th century). In discussing the supernatural darkness at Jesus’ crucifixion, Africanus writes:

“Thallus, in the third book of his histories, explains away this darkness as an eclipse of the sun—unreasonably, as it seems to me.”

— Julius Africanus, fragment in Syncellus’ Chronography.

Reference: ⬇️

https://ccel.org/ccel/juliusafricanus/extant_fragments/anf06.v.v.xviii.html

References to the darkness during the crucifixion of Jesus of Nazareth does not only comes from the biblical account but also the historically proven and documented by scribes event, apart from Thallus, other historians mention it, like Phlegon or Tertullian.

See more here.

- The next account on the Jesus of Nazareth outside of the biblical spectrum would be the fascinating ancient letter written by Mara Bar Serapion to his son that calls Jesus as a “Wise King”

“What advantage did the Athenians gain from killing Socrates? Famine and plague came upon them as judgment for their crime.

What advantage did the men of Samos gain from burning Pythagoras? In a moment their land was covered with sand.

What advantage did the Jews gain from executing their wise King? It was just after that that their kingdom was abolished.

God justly avenged these men… The wise King, because of the new laws he laid down, was not dead; he lives on in the teaching which he had given.”

— Mara bar Serapion, Letter to Serapion,

Dive deep into the Mara Bar Serapion here ⬇️

- As we have already covered and cited numerous sources supporting the historicity of Jesus of Nazareth, there are still a few more notable mentions worth addressing—such as Phlegon of Tralles, a pagan historian from the 2nd century AD, whose work appears at a striking event recorded in the Gospels: the mysterious darkness and earthquake at the crucifixion.

Phlegon’s original works are lost, but quotations from them survive in early Christian writings—most notably in Julius Africanus, Origen, and Eusebius—which point to his mention of an extraordinary darkness and earthquake.

Africanus, writing on the darkness at the crucifixion, notes:

“Phlegon records that, in the time of Tiberius Caesar, at full moon, there was a full eclipse of the sun from the sixth hour to the ninth, manifestly that one of which we speak.”

— Julius Africanus, Chronicle, fragment preserved in George Syncellus’ Chronography

In Against Celsus, Origen responds to a pagan critic by citing Phlegon:

“Now Phlegon, in the thirteenth or fourteenth book, I think, of his Chronicles, not only ascribed to Jesus a knowledge of future events…but also testified that the result corresponded to His predictions. With regard to the eclipse in the time of Tiberius Caesar, in whose reign Jesus appears to have been crucified, and the great earthquakes which then took place…”

— Origen, Against Celsus, 2.33

In his Chronicle, Eusebius summarizes Phlegon’s account:

“In the fourth year of the 202nd Olympiad [AD 32–33], there was the greatest eclipse of the sun, and it became night in the sixth hour of the day so that stars appeared in the heavens; there was a great earthquake in Bithynia, and many things were overturned in Nicaea.”

— Eusebius, Chronicle (Jerome’s Latin translation)

Phlegon was not a Christian; yet his historical chronicle records a darkness and earthquake during the reign of Tiberius—precisely the timeframe of Jesus’ crucifixion.

- Although Lucian of Sasosata doesn’t mention Jesus by name, his satire in “The Passing of Peregrinus” serves as a vital external, hostile witness to early Christian belief—particularly belief in Jesus' divinity and the persecution they embraced.

Lucian mocks how Peregrinus used Christianity as a vehicle for fame and status, noting:

“He beaconed fame to himself by attacking the Christians and behaving as their proud teacher… and he consorted with them and called Jesus, their god, to witness that he too was a Christian.”

And later, “He got himself thrown into prison and so endured a short spell of punishment with glory.”

in other place is written,

“The Christians, you know, worship a man to this day,–the distinguished personage who introduced their novel rites, and was crucified on that account…. You see, these misguided creatures start with the general conviction that they are immortal for all time, which explains the contempt of death and voluntary self-devotion which are so common among them; and then it was impressed on them by their original lawgiver that they are all brothers, from the moment that they are converted, and deny the gods of Greece, and worship the crucified sage, and live after his laws.”

Lucian’s mocking Christians is valuable because he is not sympathetic. His reference to Jesus as “their god” demonstrates that Christian belief in Jesus’ divinity was well-rooted enough to be ridiculed among skeptics.

- Another ancient source that portrays early Christianity that’s worth mention would be Celsus.

Celsus is a classic example of a hostile, informed witness whose criticisms confirm the very reality apologists want to establish: that Christianity was an identifiable, public, and theologically challenging movement in the Roman world.

Celsus, a Greek philosopher of the second century, authored a treatise titled The True Doctrine in which he sharply criticized Christianity. Although the original work has not survived in full, much of its content is preserved through quotations found in Origen’s rebuttal, Against Celsus, when it’s said:

“…in imitation of a rhetorician training a pupil, he [Celsus] introduces a Jew, who enters into a personal discussion with Jesus, and speaks in a very childish manner, altogether unworthy of the grey hairs of a philosopher, let me endeavour, to the best of my ability, to examine his statements, and show that he does not maintain, throughout the discussion, the consistency due to the character of a Jew. For he represents him disputing with Jesus, and confuting Him, as he thinks, on many points; and in the first place, he accuses Him of having “invented his birth from a virgin,” and upbraids Him with being “born in a certain Jewish village, of a poor woman of the country, who gained her subsistence by spinning, and who was turned out of doors by her husband, a carpenter by trade, because she was convicted of adultery; that after being driven away by her husband, and wandering about for a time, she disgracefully gave birth to Jesus, an illegitimate child, who having hired himself out as a servant in Egypt on account of his poverty, and having there acquired some miraculous powers, on which the Egyptians greatly pride themselves, returned to his own country, highly elated on account of them, and by means of these proclaimed himself a God.” - Documentation available here ⤵️

https://www.earlychristianwritings.com/text/origen161.html

- The last source of significance for establishing the historicity of Jesus of Nazareth and the early Christian movement would undoubtedly be early Christian documents written outside the Biblical canon.

The decades immediately following the life of Jesus of Nazareth were a formative period for Christianity. While the New Testament itself contains primary eyewitness testimony, an additional layer of historical credibility is provided by early Christian writers—leaders, apologists, and pastors—whose works circulated between AD 50 and AD 157. These figures not only reinforced the events recorded in the Gospels but also engaged opponents, preserved apostolic teaching, and connected directly or indirectly with those who personally knew the apostles. Their writings offer strong historical grounding for the Christian faith.

Let’s cover first one of the most important christian sources ➡️ The Didache (c. AD 50–70)

One of the earliest non-canonical Christian writings, The Teaching of the Twelve Apostles called Didache outlines early church practices, moral instruction, baptism, and the Lord’s Supper. Its early date and close reflection of apostolic teaching suggest it arose within living memory of Jesus ministry.

It affirms the reality of Jesus teachings and the immediate organization of the Christian movement.

Clement of Rome, a leader of the church in Rome and possibly the Clement mentioned in Philippians 4:3, wrote a letter to the Corinthians (1 Clement) urging unity. He cites the resurrection of Jesus as a historical event and draws on multiple apostolic traditions.

Clement was a contemporary of some apostles, providing a near-firsthand witness to early Christian belief.

“Let us consider the wonderful sign which is seen in the regions of the east… the resurrection of the Lord…” - 1 Clement 24.

Notable mention is the disciple of the Apostle John, Polycarp’s Letter to the Philippians reinforces the death and resurrection of Jesus and echoes apostolic doctrine. His martyrdom account (The Martyrdom of Polycarp) also reflects a strong belief in the risen Christ.

His direct connection to John links him to an eyewitness of Jesus’ ministry.

Another disciple of the Apostle John, Ignatius wrote seven letters on his way to martyrdom in Rome. He consistently affirms Jesus’ historical life, crucifixion under Pontius Pilate, and resurrection.

For example, in Letter to the Smyrnaeans 1:1–2, Ignatius warns against Docetism (the belief that Jesus only seemed human), insisting that Christ “was truly born, and ate and drank, was truly persecuted under Pontius Pilate, was truly crucified and died.”

Ignatius’ insistence on the physical reality of Jesus’ life and death shows that the earliest Christians considered these historical facts non-negotiable.

Another important historical account of the early church ➡️ Papias, bishop of Hierapolis, gathered oral traditions from those who had known the apostles. Although his work survives only in fragments quoted by later writers (such as Eusebius), he records information about Mark’s Gospel being based on Peter’s firsthand testimony and Matthew’s compiling of Jesus’ sayings in Hebrew.

Papias explicitly connects the Gospels to apostolic eyewitnesses, strengthening the historical reliability of the New Testament accounts.

These early Christian writers were not creating myths decades or centuries removed from the events—they were documenting, defending, and living out their faith in the shadow of living memory. Their works serve as powerful historical anchors, demonstrating that belief in the crucified and risen Jesus was not a later invention but an unbroken conviction rooted in eyewitness testimony.

Together, they form a cumulative case for the historical reality of Jesus Christ, standing alongside secular sources like Josephus, Tacitus, and Pliny the Younger. For the Christian historicity, they are indispensable in showing that the Jesus of faith is also the Jesus of history.